Below, Gabe Kaplan — cocreator and star of Welcome Back, Kotter — reminisces about the show’s highs and lows half a century later, with a little help from Michael Eisner, Lawrence Hilton-Jacobs, John Sebastian, James Woods and its breakout star, John Travolta.

It’s been 50 years since Welcome Back, Kotter premiered. I’m 81 now, and my afro and flat stomach are distant memories, but whether or not I’m carrying my Sweathogs lunchbox, strangers still recognize me as Mr. Kotter. When we launched in 1975, linear TV was the only game in town. Cable was still new, and there was no internet or social media — just three major networks and the possibility of huge Nielsen numbers.

Popular stand-ups had been starring in sitcoms for years, and their characters had varied occupations. Bob Newhart became a psychologist, Don Rickles a chief petty officer and Don Adams — would you believe? — a secret agent. For whatever reason, no comic had starred in a sitcom based on their own material.

In 1973, after doing stand-up for more than 10 years, I was still trying to get a spot on the mecca for stand-ups, The Tonight Show. The comedy booker, Craig Tennis, had turned me down twice. I’d auditioned with what I thought was great TV material, but Johnny’s couch would have to wait.

One night at the New York Improv, I was doing material much too far out for ’70s TV, like impersonating Howard Cosell broadcasting the crucifixion. Mr. Tennis was there and liked it, and presto — I was on The Tonight Show that week, doing the same material he’d rejected twice. Television is a crazy business.

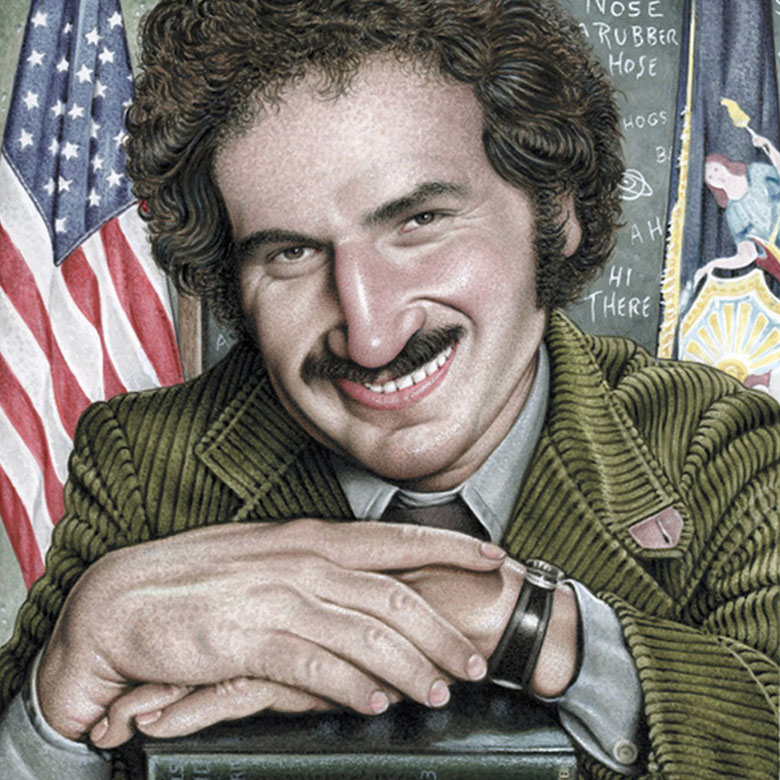

Illustration by Drew Friedman

In the year that followed, I was on talk shows, variety shows and several summer replacement variety shows (The Mac Davis Show, The Gladys Knight & the Pips Show, Lola! and others). In the 1970s, if your album cracked the Top Five, you got a summer replacement show.

One night, after my set at the Comedy Store, a little guy with a big smile introduced himself to me in very slow Brooklynese: “Hi Gabe. I’m Alan Sacks.”

Don’t ask me how, but it took him 30 seconds to get through that. He sped up as he explained that he was the producer of Chico and the Man and wanted to talk about my future TV plans. He was there with Chico star Freddie Prinze, who was about to go on. Alan said he’d call.

True to his word — and very un-showbiz-like — Alan called the next day to ask if I was free. I had big plans with the dry cleaner and then, if I still had energy, my dirty dishes, but I said I’d move things around.

At Joe Allen’s that afternoon, I asked Alan if anyone had ever turned their act into a sitcom. He said not to his knowledge. I started talking about my high school buddies, a mainstay of my act. We began spitballing ideas. The first was about five guys who went to school together and never grew up, still acting 18 when they were 28. But how would it work? What would the main set be? Would I play myself?

“What if I wasn’t their peer?” I asked. “What about a guidance counselor?” We went with that for a while, then the counselor became a teacher, and then the teacher became an alumnus who had also been an underachiever. In one long, two-hamburger lunch, we created our show. The waiter eventually sued for profit participation.

I wrote the treatment, and then we made some changes — with Alan, not the waiter, who was becoming difficult. Everyone who read it loved it. Alan was ready to show it to his boss, Chico’s executive producer, James Komack.

Jimmy K. had a long history in the biz. He’d been an actor, a writer and a musical comedy performer. By that point he was also the creator and producer of two hits, The Courtship of Eddie’s Father and Chico. But he’d started out as a stand-up. This was great news — I had real chemistry with most comedians his age, like Shecky Greene and Buddy Hackett. I’d come up the old-fashioned way, working similar clubs and having experiences like theirs. I imagined the superlatives he’d lay on the treatment: “Innovative, foundational … just what television needs.”

His reaction, Alan reported, was slightly different. “This might be the worst idea for a show I’ve ever heard,” Jimmy K. said, but Alan thought we had something good, and he wasn’t giving up. I liked his attitude, and I loved that he told me all this in 20 seconds.

Michael Eisner, the future CEO of Paramount and Disney, was then heading up programming at ABC. Alan knew him and was able to set up a meeting. Eisner was aware of me and very interested in doing a show with Jimmy, who told Alan to go ahead with the meeting if he wanted to make a fool of himself.

But Eisner loved the treatment. He ordered the pilot script, with just one note: We had five students, including a Puerto Rican and a Jew. He thought five was too many and suggested we make one character a Puerto Rican Jew. We loved it.

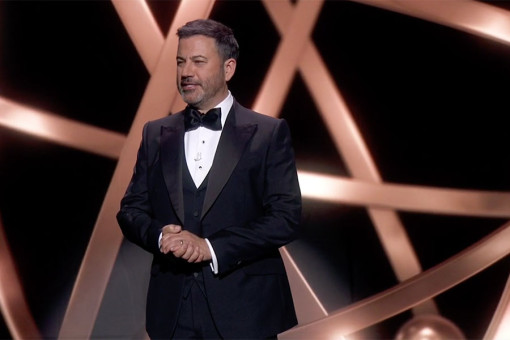

Photo credit: Photofest

Peter Meyerson had cowritten the pilot for The Monkees, and ABC picked him to write ours. He finished it in a month. He improved on the treatment, introduced all four guys in a hilarious way and even came up with the name “Sweathogs.” They had hired the right guy.

The network read it and ordered a pilot. Suddenly, Jimmy became totally immersed in the worst idea he’d ever heard. His whole team descended on the project. He then asked Alan why he hadn’t met me yet.

When I arrived at Jimmy’s house in the flats of Beverly Hills, Alan was there. Jimmy was not what I expected. He had longish hair and a walrus mustache. He looked larger than life. He had kind eyes and reminded me of an eccentric uncle who would reach into his pocket, jingle some change around and come out with about 50 cents for you. He sipped on a martini and smoked Nat Shermans. A lot of them. Boxes were scattered all over the house. He spent the first 15 minutes telling me how great my “twinkle” was. I responded that I thought he had a great twinkle, too. When our twinkle-off ended, we started talking about the show.

He said he’d direct the pilot, and Lynn was going to cast it. “Lynn Swann?” I asked. Without smiling, he said, “No, Stalmaster.” I made a mental note: no sports jokes. We agreed Meyerson’s pilot was great, and Jimmy asked what I liked most about it. I said, "What’s really good is we can use the ethnic diversity when it fits and leave it alone when it doesn’t.” Alan nodded in agreement, but Jimmy did not look like he was on board.

This seemed strange. He’d created Chico, a show based on diversity, and it was the era of All in the Family and The Jeffersons. He thought for a second and said, “I could start a joke with ‘Two Jews get off a camel,’ but it’s just as funny if I say ‘Two jerks get off a camel,’ and it doesn’t offend anybody.” I must have missed the setup. Why were Jews getting off camels? He looked at us like we should be impressed by his sage wisdom, then added, “These kids are like Our Gang; nobody will care about ethnic diversity. It’ll be a distraction.” Alan just sat there, looking like he’d rather be in Bangladesh.

Suddenly, the meeting was over. Jimmy said, “Well, this has been a good first meeting. I wouldn’t describe it as great, but that’s okay.” Which seemed to mean it wasn’t okay. Not to him and not to me either. The network liked the pilot, so why was he trying to vanilla things up? Did I act incorrectly? Was I supposed to go along with whatever he said? It didn’t seem like he’d really thought about this.

A few days later, I was invited back. I was relieved; perhaps we could clarify what we both were feeling. It was just the two of us this time. To get things rolling, I’d brought Neil Diamond’s song “Brooklyn Roads” to pitch as a theme song. We played it, and he said, “That’s a great song.” He clearly had zero interest in it. He had something else to discuss.

Jimmy told me the network didn’t want ethnic diversity on the show. That made no sense. They wanted a Puerto Rican Jew, an Italian, an African American and the mystery of whatever Horshack was to be together every day, dealing with other students and each other’s families in 1975 Brooklyn. All this, without any racial tension? I wondered what kind of conversation he’d really had with the network. Anyway, I’d lost the battle before it began. I asked if he intended to change the pilot script. He said no. That was at least something.

The complete version of this article can be found in emmy magazine, issue #9, 2025, under the title: "High School Confidential."